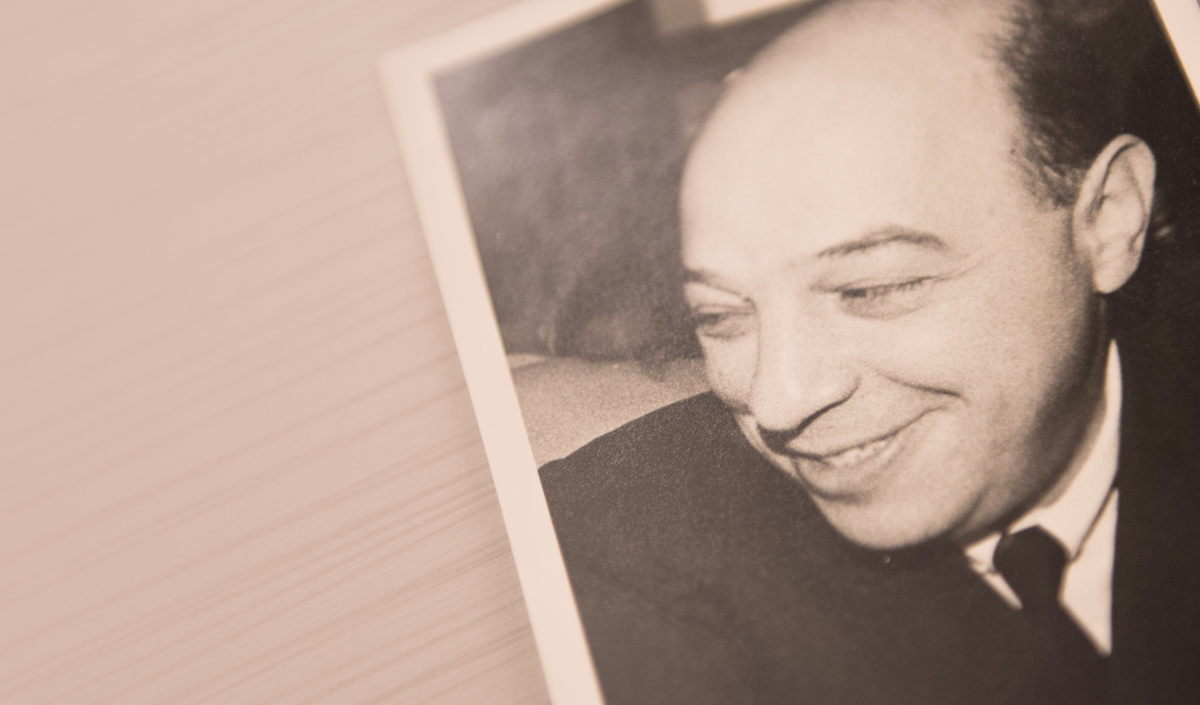

While still a student at Duquesne University, alumnus Louis D. Mallet (B’40) started a business developing new products for the baking industry. His company, the Home Kitchen Company, launched in 1939 with one truck and one employee, working out of his mother’s kitchen and a rented garage. Ten years later, Louis changed the name of the firm to Mallet & Company, Inc. Thanks to his tremendous entrepreneurial spirit, persistence and desire to succeed, Mallet & Company steadily grew into a multi-million dollar business, sourcing and selling products and equipment worldwide.

Duquesne saw the potential in Louis

The son of an immigrant family from Russia, Louis was the first in his family to speak English. Growing up in a household where Russian was spoken, Louis was not only determined to learn English, but to seize new opportunities, and to start a new life in America. He believed that the key to a better life was education and economic independence.

In 1931, Louis began his nine-year journey at Duquesne. His father gave Louis forty dollars, which was Duquesne’s registration fee at the time, telling him that was the sum total of what he could afford to contribute toward Louis’ education. In short, the family had no other money to pay for tuition. But this didn’t deter Duquesne from recognizing that Louis had great potential and just needed some help—consistent with the assistance the university has provided to many sons and daughters of immigrants over the years.

So Duquesne worked out a “dollar-down and a-dollar-when you-can-get-it” informal tuition plan and offered Louis a work-study program to boot. Louis attended classes in the morning, sold yeast to local bakeries in the afternoon and studied in the evening. In 1940, he earned a Bachelor of Science in Business Administration with a concentration in Economics.

“The reason why I gave a gift and volunteered to teach in the Palumbo-Donahue School of Business is because Duquesne took a chance on my dad. He didn’t have any tuition money. Duquesne worked out a dollar-down and a-dollar-when you-can-get-it kind of tuition plan. I don’t think you see that generosity very often, if ever,” said Robert Mallet, son of Louis D. Mallet, Former Chairman, Mallet & Company.

Louis risked everything to follow his passion

Louis became thoroughly familiar with the baking industry and studied the challenges facing his customers. He recognized various customer needs that the giant baking suppliers were simply failing to meet. For instance, when cellophane overwrap replaced the boxing of cake, it was a terrific invention. However, the cellophane overwrap caused significant problems with melting, sticking, and the breakdown of icing on baked goods.

Louis felt that “the icing sells the cake.” So he began experimenting and researching ways to enhance the appearance, texture and shelf life of icing. Seventy-seven experiments later, he solved the problem. He called it P.I.C. 77, which stood for “perfect icing conditioner” and the number of tests required to discover a solution.

A true visionary, Louis decided to take a huge risk and invest $900 to manufacture P.I.C. 77. The money came from his loving girlfriend who turned out to be his future wife, Dorothy. It was a prescient decision and his product was an immediate success! This move underscored one of the core principles that Louis built his successful business on—giving customers what they want.

Louis believed that failure was key to success

During WW II, Pittsburgh was filled with immigrants, mainly from Europe. The immigrant population in Pittsburgh wanted rye bread, but there was a domestic shortage of caraway seeds due to the war. Giving customers what they wanted, Louis decided to manufacture his own seeds since there were none available. The ingredients included flour, water, seasonings and black food coloring. The process involved using a high-pressure pump to push the mixture through little holes in a brass die that were then sliced and dried. One side of the brass die included round holes and the other side moon slivers to resemble the shape of caraway seeds. Ultimately, Louis produced seeds that looked and tasted authentic. However, during the mixing process, the seeds melted in the mixture and stained the bread black.

Disappointed in the outcome, Louis used this experiment as a valuable learning experience. He kept the brass die on his desk as a reminder that failure is a necessary part of growth. Indeed, the brass die sat on the desk of three family owners of Mallet & Company for a period of 77 years to remind each one that failures are valuable lessons that can lead to success.

Exemplifying integrity, Louis drove 40 miles to return 35 cents

Another core principle that Louis Mallet lived by was integrity. Robert Mallet recounts an incredible story about his father’s absolute integrity and unshakeable honesty. When he was ten years old, Robert remembers driving with his father from their farm in Ligonier to their home in Squirrel Hill. They took the turnpike from Irwin to Monroeville. Even though it was a school night and getting late, Robert persuaded his father to stop at Howard Johnson’s on the turnpike to buy him an ice cream cone, which cost 35 cents. Oddly enough, the turnpike toll was also 35 cents.

When they reached Monroeville, Louis had no change to pay the toll. He had spent the 35 cents in change on Robert’s ice cream. All Louis had was a $100-dollar bill which he gave to the man in the toll booth. The man waived him through and said, “I’m not giving you $99.65 change for the toll. You can go.” Robert saw that his father was upset. Louis drove home, got 35 cents and returned to Monroeville to pay the man who waived them through. Robert said, “This is a story I will never forget. We drove 20 miles each way to pay 35 cents to the Pennsylvania Turnpike Commission. This is the way the Mallets grew up. This is the way my father ran his life, his business and his family. Integrity, honesty and forthrightness were paramount. You could not look yourself in the mirror if you weren’t 100 percent honest.”

An incredible legacy

Louis was as successful a family man as he was a businessman. He and his wife, Dorothy, instilled in their four children a hard-work ethic and absolute integrity. Louis put his heart and soul into everything he did, including his children’s goals and ambitions. When his daughter Eleanor, who was 15 at the time, wanted riding lessons, he took lessons, too. And when she wanted a saddle horse, Louis bought two—one for her and one for himself! As he did in business, Louis became a knowledge-seeker. He enjoyed learning everything he could about horses. In time, he purchased enough horses to populate a farm in Ligonier and engage in harness racing.

Duquesne may have taken a chance on Louis, but in retrospect, the University was fortunate to have such an incredible graduate. Louis gave back to Duquesne by sharing his inspirational story with students. In 1955, Clarence Walton, dean of the Business School, invited Louis to speak and then followed-up with a letter that stated, “The very fact that you were an alumnus served as an inspiration for these young people. In talking with many of them, your name recurred frequently. It was the sort of theme which revolved around these words: If he could do it maybe so can I.”

“Louis is the perfect role model for future generations of Duquesne students. The School is very grateful for the philanthropic support from Robert Mallet and the Mallet Family. Their generous gift will be a dynamic force behind the School’s Center for Excellence in Entrepreneurship and the incredible transformation ahead of us,” says Dr. Dean McFarlin.